Deterministic Commitment of Bitcoin Transactions and Addresses

Introduction

Bitcoin works by keeping track of unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs). These are the outputs of transactions that have not been spent yet. When a transaction is created, it consumes some UTXOs and creates new ones. The new UTXOs can be spent by other transactions, and so on. The UTXOs are stored in the UTXO set. A wallet is a collection of UTXOs that can be spent by the wallet owner, usually by signing a transaction that consumes the UTXOs.

In the original Bitcoin whitepaper, Satoshi introduces two types of clients: a full node and a SPV node. To Satoshi, a full node is a client that validates the network state against all consensus rules, and collects transactions from a pool of unconfirmed transactions, and commit to them by generating enough PoW to produce a block. SPV, a shorthand for Simplified Payment Verification, is a client that does not validate the network state, but instead relies on a full node to do so. SPV clients are only interested in the transactions that affect their wallet, and so they only download the blocks that contain transactions that affect their wallet. SPV clients are also called lightweight clients.

Figure 1: Satoshi defines a node as a client that validates the network state against all consensus rules, and is capable of generating blocks.

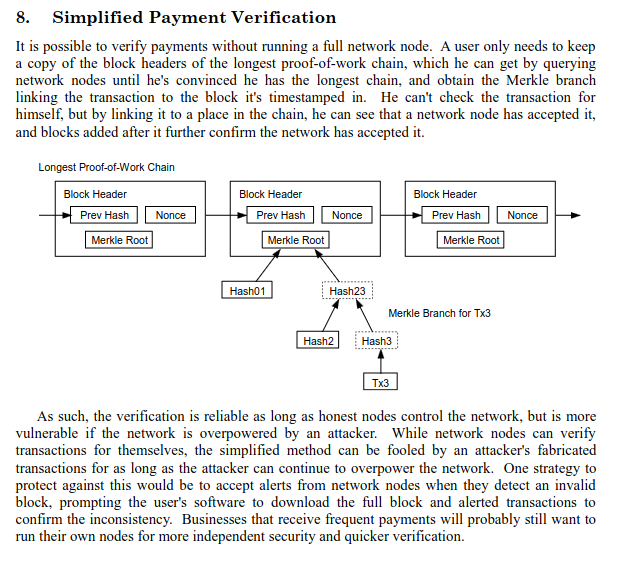

Figure 2: He also introduces SPV nodes, that is how clients would interact with the network, not requiring the full blockchain.

The SPV nodes gets their security from the so called Nakamoto Consensus - Named after Satoshi Nakamoto, ofc. The Nakamoto Consensus is a probabilistic consensus that relies on the fact that the majority of the miners are honest, it is probabilistic because it is possible for an attacker to produce a longer chain than the honest chain, but the probability of this happening decreases exponentially with the number of blocks that the attacker has to produce.

The Bitcoin Whitepaper gives some weird math to compute the probability of an attacker producing a longer chain than the honest chain, by modeling it as a Poisson process, but I will not go into details here. He even gives a C code to compute the probability, but I will not go into details here either. But here is it (won’t put the equation because I didn’t put the mathjax in this blog yet):

#include <math.h>

double AttackerSuccessProbability(double q, int z) {

double p = 1.0 - q;

double lambda = z * (q / p);

double sum = 1.0;

int i, k;

for (k = 0; k <= z; k++) {

double poisson = exp(-lambda);

for (i = 1; i <= k; i++)

poisson *= lambda / i;

sum -= poisson * (1 - pow(q / p, z - k));

}

return sum;

}

An SPV proof is a Merkle Path to the tree’s root. Imagine the following Merkle Tree:

06

|-------\

04 05

|---\ |---\

00 01 02 03

The nodes at the bottom are the hashes of our original element, in this case, the hash of each transaction in the block. You then pairwise hash the leafs to get the next level. In this case 00 and 01 are hashed to get 04, and so on. The root is the hash of the two hashes at the top. In this case, 04 and 05 are hashed to get 06.

If you want to prove that 00 is in the tree (therefore, in the original set), you just need to disclose the hashes 01, 05. The verifier is then able to compute the root hash by hashing 00 and 01 to get 04, and then hashing 04 and 05 to get 06. The root of the tree is in the block header, and so the verifier can check whether the root is the same as the one in the block header or not. The block header is protected by PoW, and so the verifier can be sure that the block header is valid (assuming that the majority of the miners are honest).

That’s great, but we have a problem. How does a wallet finds out whether the did get some funds or not? The Bitcoin Protocol don’t define any mechanism for a wallet to find out whether it has received some funds. The only way you can find that out is by downloading all the blocks and checking by yourself, or using some overlay protocol like Electrum (formerly known as Stratum). The problem with the Electrum Protocol is that there’s no way a SPV node can know whether the Electrum server is lying to it or not. The SPV node has to trust the Electrum server to not lye about not having a tx, and that’s not good.

Moreover, they tends to be very privacy invasive, holding multiple of your addresses and therefore, knowing your entire transaction history. That’s not good either. This hurts the very privacy that Bitcoin was designed to provide.

Solutions?

Bloom Filters

How can we solve this? Well, it’s not a simple problem to solve, and many attempts have been made to solve it. One of such attempts is the BIP37 Bloom Filters. The idea is that the SPV node sends a probabilistic data structure that tels whether a value matches a set or not. The set of interest is all spks in a wallet. Being probabilistic means that it may return false results randomly. Bloom Filters have false-positives, that is, it says definitely no or maybe yes.

The idea is to send a filter that matches with the wallet’s transactions, and some junk. The spurious matches are also sent to the client, and the node have no way to know whether the transaction is a spurious match or not. The SPV’s privacy is protected because the full node does not know which transactions the SPV node is interested in, just a pool of possible transactions.

The problem with this approach is that it is very easy to deanonymize the SPV node, e.g by sending a bunch of transactions and waiting for the SPV node to request them, it’ll only request the transactions they are interested in, and therefore, breaking the anonymity of the protocol.

Neutrino - BIP157 and BIP158

Another attempt to solve this problem is the BIP157. This flips the filtering idea from the node to the client. The node builds a static filter containing all the block’s data. The client then downloads the filter and checks whether something interesting is in a block or not. The client then downloads the block and checks whether the transaction is in the block or not. This is called a client-side filtering.

The first (and as of today, the only) implementation of client-side filtering is BIP158. It uses Gallomb Rice codes to compress the data in a probabilistic filter. The filter is then sent to the client, which then checks if there’s something interesting in the block. If there is, the client downloads the block and parses what it is interested in.

The problem with this approach is that it is very bandwidth intensive. The client has to download the entire block to check whether there’s something interesting in it or not. The filters are also somewhat bit, and the client has to download all filters for all blocks.

Deterministic Commitment

Now hear me out: What if we could commit to the spk of (and txid?) of transactions in the block header, in a deterministic way, protected by PoW?

Deterministic commitment is a form o commitment that allows you to find the position of something without looking at the set. The advantage of this is that if you know where something should be, and if I prove you that there’s something else there, you can be sure that the thing you’re looking for is not there.

Imagine that we have a deterministic way of building a Merkle Tree, and we commit to the root of the tree in the block header. The client can then download the block header, and check whether the transaction is in the block or not. To check whether the transaction is in the block or not, the client has to download the block header, the transaction and a spv proof for this tx. The proof is a set of Merkle Proofs showing what is in the position of it’s spks, for each block. If you’ve got a tx, you’ll see it in the proof, if you didn’t, you won’t see it in the proof. It’s that simple.

Some numbers

Let’s assume that the Bitcoin network has 1,000,000 blocks. If each hash is 32-bytes long, how many bytes to prove the history of a spk?

Also assuming 20k outputs per block, this yields trees with ~15 levels. The proof for a single spk is 15 hashes, or 480 bytes. Now you make 480 * 1,000,000 blocks, and you get 480,000,000 bytes, or 480 MB. That’s a lot of data, but it’s not that much. But this is the absolute worst case scenario, where you have to prove the entire history of a spk from genesis.

Here are some ways to reduce this number:

The first one isn’t really a thing we do, but the first few blocks are pretty empty, so we can assume that the first 100,000 blocks are almost empty, and therefore, we can assume that the first 100,000 blocks are 1/5 of the size of the other blocks, and therefore, we can reduce the size of the proof by 1/5, or 96 MB.

Moreover, it’s very unlikely that your wallet has outputs from the very old blocks, so we can just skip the first n blocks, and therefore, reducing the size of the proof by n * 480 bytes. If your wallet is p2tr, we can skip to the first taproot block, which is block 709,632, and therefore, reducing the size of the proof by 480 * (1,000,000 - 709,632) bytes, or 134,000,000 bytes, or 134 MB. We would then have a proof of 346 MB.

Finally, if you can use a zkSNARK to prove that you have a valid history, and that the only outputs to this spk are the ones the node is waving at you, you can reduce the proof to a constant size, sub-MB proof. The node will do some extra work, but it’s not that much, and the robustness of the protocol is greatly increased.

A very simple example

Here’s a super simple example of deterministic commitment, borrowed from here. The scheme is simple.

- Pick a number

nsuch thatn >> M, whereMis the number of elements you want to commit to. E.gn = M * 2 - For each element

- Compute h = id % n, where this id is some form of commitment to the element, represented as a number

- Check if the position

his empty- If it is, put the element there

- If it isn’t, go back to the first step with

n = n * 2

- The commitment is

nand the root of a merkle root of the elements, including the empty ones

The proof is just a simple Merkle Proof.

This is just like a non-minimal perfect hash function, but it’s not a hash function with deterministic indexing. The problem with this approach is that it’s not very space efficient, it may require a considerable amount of space for big sets. But can easily be optimized, like by using bitfields for the positions, and not allocating empty positions.

When someone sends you a Merkle Proof for block b, you can recompute the root by hashing the nodes up, and then checking whether the root is the same as the one in the block header. If it is, the proof actually tells what is in that position. The prover can’t lye, because as we move up, we need the position to check whether a node is a left or right node, and if the prover lies, the position will be wrong, and the root will be wrong.

See in the tree used above:

06

|-------\

04 05

|---\ |---\

00 01 02 03

If the element was in position 00, but the prover gives me a proof for 02. I’ll compute the root as h(02, 03), and h(05, 04) because the bit 1 of my position is 0, telling me that what I just computed is a left node. But what I should’ve computed is h(04, 05). This yields a different root, and therefore, the proof is invalid.

A proof of history of an address is a Merkle Proof for each block, simulating that the address is in the position of the spk. If the address is actually there, that means we’ve got a transaction. If there’s something else there, that means we didn’t get any tx, because if we would’ve gotten a tx, n would’ve been different, we can’t have collisions, and therefore, the position would’ve been different.

This process is less intractable than it looks, because it can be massively parallelized. You can compute the Merkle Tree for each block in parallel, and then you can also have some optimized data structure for the block’s Merkle Trees, so you don’t have to recompute the entire thing every time. After you’ve computed all proofs, you can run the following Python pseudoscope in a zk proving system and get a succinct proof about the address’s history.

def verify(spk: bytes, proofs [Proof], known_blocks: [BlockHash]) -> bool:

for i in range(proofs):

# If the spk is in a block, the prover **must** disclose the txid

if proof[i].target == spk:

# checks if the target is in one of the blocks in a disclosed list

# this list is sent by the prover

if not is_a_known_block(blocks[i]):

return false

if not verify_merkle_proof(proof[i]):

return false

return true

Now that we know what blocks to look, we just need to download the blocks and find the transaction that we want. If you use different addresses for each transaction (which you should), you will have to download at most one block per transaction. Moreover, if your wallet is somehow sane, you’ll only receive a tx in address n about the same time as n - 1, so if n - 1 have a tx, start your proof at that block height.

What about the txid?

We could use the same idea for txids, which is just making the existing Merkle Tree conforming with the deterministic constraint. And the advantage is the same: if we ask if the tx with txid was included in a block, the prover may lie, telling you that it wasn’t, but it actually was. With this scheme, the prover can’t lie. In a summary, this is a anti-DoS mechanism for wallets.

Then why don’t we just do that?

I wish we had an easy way to do that, but the most optimal way to do that is to update the block header itself. And this is (beware of a scary word that triggers many people) a hard fork. We can’t just update the block header, the entire network has to agree on that. And this is not an easy thing to do.

There’s a middle ground that is soft-forkable, but it’s not as good as the hard fork. The idea is to use the coinbase transaction to commit to the Merkle Trees. The problem here is that the client either needs to process all coinbase and keep the Merkle Trees, or the proof would have to include an spv proof for the coinbase transaction. However, this is not that bad, specially if we use a zkSNARK to prove the entire thing.

Conclusion

The current SPV protocol have some flows, and it’s not very private. There are some attempts to solve this problem, but they still have a few problems. A interesting solution is to use deterministic commitment, but it’s not easy to do that. To actually have PoW protection, you either need a soft-fork or a hard-fork to do that. The soft-fork is more resource intensive than the hard-fork, but it’s still better than what we have today.